Experiences And Challenges From Developing Cyber Physical Systems In Industry Academia Collaboration

The title of this paper is Experiences and Challenges from Developing Cyber-Physical Systems in Industry-Academia Collaboration and it was written by Johan Cederbladh, Romina Eramo, Vittoriano Muttillo, and me Per Erik Strandberg. It was published in the Wiley journal Software: Practice and Experience in January 2024 [1] .

Abstract

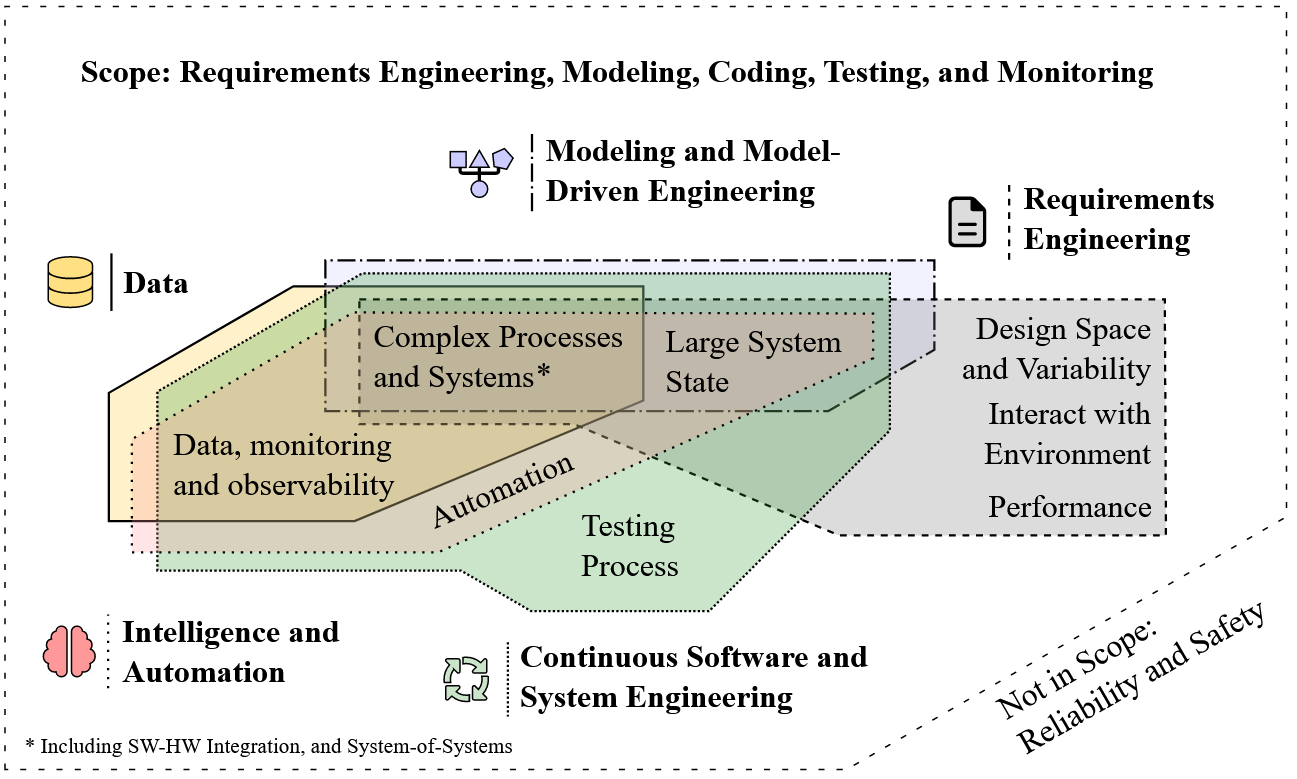

Cyber-Physical Systems (CPSs) are increasing in developmental complexity. Several emerging technologies, such as Model-based engineering, DevOps, and Artificial intelligence, are expected to alleviate the associated complexity by introducing more advanced capabilities. The AIDOaRt research project investigates how the aforementioned technologies can assist in developing complex CPSs in various industrial use cases. In this paper, we discuss the experiences of industry and academia collaborating to improve the development of complex CPSs through the experiences in the research project. In particular, the paper presents the results of two working groups that examined the challenges of developing complex CPSs from an industrial and academic perspective when considering the previously mentioned technologies. We present five identified challenge areas from developing complex CPSs and discuss them from the perspective of industry and academia: data, modeling, requirements engineering, continuous software and system engineering, as well as intelligence and automation. Furthermore, we highlight practical experience in collaboration from the project via two explicit use cases and connect them to the challenge areas. Finally, we discuss some lessons learned through the collaborations, which might foster future collaborative efforts.

Keywords Cyber-Physical systems, Industry-academia Collaboration, Lessons learned, Challenges

Lessons learned

Towards the end we summarize a lessons learned in a Table:

- Joint Problem formulation: Due to the different stakeholders in academia and industry it is common to work towards closely related but in the end separate goals. Effort should be spent on identifying dissemination strategies that can fulfill the needs of all involved parties, preferably without disjoint parallel activities.

- Common value formulation: For academic partners, value might come from examining and comparing academic solutions in the company settings (preferably disseminated in publications), whereas value for industry partners could come in the form of knowledge, process improvements, prototypes, etc. Collaborations should strive for maximizing value from both perspectives.

- Hackathons: Hackathons could be described as a time-boxed exploration of a problem or data set. These can bridge the gap between industry and academia, and rapidly show the feasibility of research questions e.g., "are there test cases that pass and fail together?". Hackathons can also promote the "show not tell" principle by rapid- prototyping through intensive shared work with involved partners.

- Share data: Sharing data can speed up industry-academia collaboration. However, industry partners may find this difficult due to resource constraints, implementation effort, data retention and pruning, as well as for information security concerns. Sometimes simply having a small set of "real" data in the beginning of a collaboration can foster trust and pave the way for gradual introduction of more data.

- Joint Work on Solution: In addition to hackathons, structured feedback and sharing data, the project could hold regular meetings with all involved partners for discussing the progression of the use case. These gives all partners part of progress and get motivated, and limits the risk of drift of focus from the original problem formulation while promoting shared responsibility of he work.

- Structured Feedback: Feedback from industry partners to academic partners could be collected in a structured way, e.g., triggered by show and not only tell. Having structured feedback in terms of surveys and extensive workshops are good practices which can directly highlight areas for improvement in the collaboration. Particularly, such feedback could extract valuable insights from a wider range of users and stakeholders, which might not be directly involved in the collaboration.

- Continue Past Project Collaborations: that work towards long term goals past project boundaries can foster trust in addition to more freedom in adaptation. Additionally, companies might be more willing to invest resources in collaborative efforts that will stand on their own in contrast to typical research projects.

This page belongs in Kategori Publikationer